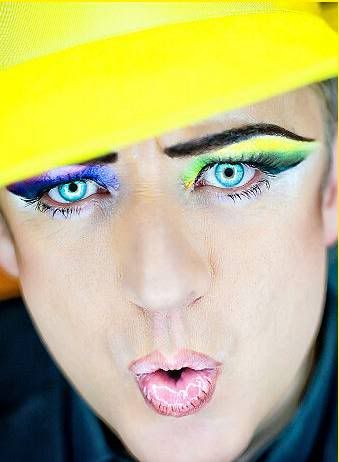

"Sober for two months and two weeks now," he beams, holding up a key fob from his 12-step programme meetings which reads, "Clean and serene for multiple years of recovery". "It's interesting being sober, because I've learnt I'm actually quite nice, after all." He chuckles again, then readjusts his felt pink Philip Treacy hat (with embroidered sequins) until only one eye is visible. "Shame it took me so long to find out."

To suggest that Boy George has had a rough time of it over the past half-decade is to understate matters somewhat. But as he will himself readily admit, without a trace of self-pity, he has mostly brought it all on himself. After 16 years of sobriety, in 2003 he fell back into the drug-taking ways that claimed so much of his life during the 1980s, and began again to use heroin, and then cocaine, frequently. It was an addiction that would land him in trouble more than once. The first time, in New York, he would end up doing community service. The second, back in London, he'd be sent to prison, ultimately serving four months behind bars.

Almost a year since his release, the 48-year-old now just wants to remind everybody, and perhaps himself, of the real reason he first became famous three decades ago. George may no longer be the pretty young thing of 1982's "Do You Really Want to Hurt Me?" – he has filled out considerably since then, while the tattoos on his neck and hands lend him a certain circus sideshow air – but he retains a wonderfully agile voice and an innate ability to perform. And though his new, solo single "Amazing Grace" can't hold a candle to his Culture Club highlights, it does contain enough infectious rhythm to suggest that he isn't quite a spent creative force just yet.

"I played nine sold-out shows here before Christmas," he says of the Leicester Square Theatre, "and it reminded me that there was still an audience out there for me – a surprisingly loyal one."

I suggest that it must have been difficult, initially at least, to face his fans after so public a downfall. Instinctively, an eyebrow curls in anticipatory combat.

"Why would it? All the feedback I've had since I've been out – on the streets, on Facebook, Twitter – has been positive, nobody mentioning prison at all. It's only journalists who do. Thank God for strangers, I say!" He laughs loudly. "Besides, what happened to me was very personal, and I have learnt, often the hard way, that less is sometimes more. I don't have to discuss everything with everybody. After all, this is my business and nobody else's, isn't it?"

He is quite right, of course, but this didn't stop his business spilling quite freely out into the public domain regardless. It all started five years ago. In October of 2005, while residing in New York, George telephoned the police to report that his Manhattan apartment had been broken into. The police arrived, but found no evidence of burglary. They did, however, find 13 bags of cocaine. George claimed the drugs weren't his, but he was charged with reporting false burglary, and given a stretch of community service. This, he had been led to believe, he would be able to conduct away from the public eye. Instead, he ended up sweeping the all-too open streets of Chinatown, much to the evident pleasure of the attendant media circus. George, innate performer that he is, simply grinned at them as if such public degradation was nothing more than water off a duck's back. '

Then, three years later, he was arrested again, this time for the false imprisonment of a male escort, whom he had allegedly chained to a radiator in his London home for several hours, and also beaten. He was later sentenced to 15 months in prison, and on 16 January 2009, entered London's Pentonville. Was he scared?

He shrugs. "Probably, yes. I thought all sorts of things were going to happen to me, and so for the first few days I was very defensive and aggressive, trying to assert myself. But people were actually really nice to me. I made friends."

After six days, he was transferred to HMP Edmunds Hill in Suffolk, a category C prison – containing inmates who cannot be trusted in open conditions but are unlikely to try to escape – where he spent the remainder of his sentence, truncated from 15 months to four for good behaviour.

"I was lucky because I didn't have to share a cell. Just as well, because I wouldn't have." But presumably he wouldn't have been given a choice? "Well, if you are considered to be a vulnerable prisoner," he suggests awkwardly, "then there is no point putting you in a cell with someone you end up fighting with – or killing – is there?"

While inside, he read all the books he had long wanted to but never made time for – Wuthering Heights, Catch-22, A Confederacy Of Dunces – and also kept a diary, wrote letters, and even penned a few songs (among them, "Amazing Grace"). One thing he didn't do, he admits, was ponder the crime that had landed him inside in the first place.

"No I didn't. Why? Was I supposed to?"

If George has done little promotion since being released, it is largely because he would rather forget all about it, and would clearly like everybody else to as well. In December, it was reported that he had applied to be a contestant on Celebrity Big Brother – as public a form of rehabilitation as the 21st century can currently offer for the famous – but his request was turned down by the Probation Service. While all he wants to do now is get on with his life, the media, he grumbles, wants him to appear penitent, remorseful. In other words, sorry for his crimes.

"Excuse me, but I think that is terribly sanctimonious," he says. "I've already been to trial, I've paid my price. Why should I have to explain myself to anybody, let alone seek their forgiveness?" He falls silent for a while, then says this: "There are certain people in my life who have done things to me that many other people wouldn't forgive. But if I can look at that person and say that they have a good heart, and that they are ultimately a good person, then I will. I am very forgiving."

Which is his way, one imagines, of asking the public to do likewise with him.

"But they already have!" he counters. "Ever since I've come out, I've had nothing but affection, everyone from the doorman at The Dorchester to taxi drivers. None of them have expected me to apologise. They just all seem really glad that I'm out, and that I'm back. It's made me realise that people do care for me. And before you ask, yes, I'm grateful for that. I am."

Throughout our conversation, George continually rubs at his 12-step key fob as if it contains talismanic properties. Perhaps it does. In order to maintain his sobriety, he has spent the past year attending meetings, often two a week. That's quite a commitment, I say. Do they ever get boring? "No. You always get something out of them," he suggests, "and they really are very helpful. Of course, I have had friends tease me about having become addicted to them, but, hey, I'd rather be addicted to the meetings than drugs, you know?"

Besides, he continues, it is important for him to associate with people who are not using. "You always have to be on your guard. I am an addict, after all, so if I'm around people who do drugs, I need to take myself out of that situation. The last time I developed my problem, I hadn't done that. I was around people who were using, and I thought I was fine. I wasn't. One evening, I just thought to myself, I'd like to try a bit of that. And... well, you know what happened next."

I ask whether one of the worst aspects of the past five years was the fact of his fall from grace being so very public, a former national treasure so thoroughly dethroned. He looks at me as though the question were a foolish one.

"I don't really do humiliation, actually," he deadpans. "Never have. But what I will say is that I have had a couple of very important bangs to the head recently, and I've taken note of them. As a result, I've moved on. It's all behind me."

Or so he hopes. But then, George always was helplessly drawn to drama. It's what came to define so much of Culture Club, a genuinely great 1980s group whose inter-band tensions played themselves out with such flamboyance that they soon resembled soap opera, George the architect of so much of it. Why?

He sighs, as if suddenly crushingly tired. "Oh, I don't know. Because of my childhood, growing up, all sorts of things. I was petulant, and always conflicted over everything: songs on the radio, politics, my own band members; you name it. I'm not like that any more. I've grown up." He laughs dryly. "I always used to hate it when people said things like that; it made me wretch. But I've realised that just because you grow up, it doesn't mean you necessarily have to become boring. I certainly haven't. All that has happened is that my desire for drama is greatly diminished. And it's a relief to be able to say that."

It couldn't have come at a better time, either. The man is soon to turn 50, after all, a landmark age that can send anyone into crisis if they're not careful. When better to get your house in order? Also, a renaissance of sorts might just be on the horizon. The BBC is about to screen a film called Worried About the Boy, based on the very early days of Culture Club, specifically George's tempestuous relationship with drummer Jon Moss, a relationship that Moss, now married with children, spent years denying had ever taken place.

The pair met up recently on the set of the film, and surprised one another by actually getting along. That said, at the very mention of Moss now, George cannot help but offer up a tart and tightly puckered smile, the ghost of petulance past suddenly very present once more. "He used to be able to make my blood boil within five minutes, Jon. He still does, of course – ha, ha – but I deal with it differently these days. We've actually become really good friends – as a result of the film, I suppose. That and the fact that we are older now. The wonders of maturity, eh?"

George is also currently working on a batch of songs he hopes to release as an album before the end of the year, and has just collaborated with Mark Ronson on the über- producer's forthcoming new album.

Would he welcome another shot at the limelight?

"I'd be lying if I said it wouldn't be wonderful to have another number-one single, because of course it would," he admits. "But that kind of thing only happens to people like me these days by happy accident. Most of my peers still making records today aren't making the kind of records they want to make; they are making them because they think it will give them hits. I've never been interested in that. I could, I suppose, hook up with some briefly trendy young group, N-Dubz or somebody, but that's not why I started to make music in the first place. It might surprise people to learn," he suggests with a sardonic smile, "but I'm quite into my art form, you know?"

For the meantime, then, George will continue to occupy his perennially colourful periphery. He still DJs around the world (he is big in Italy, by all accounts), and runs a monthly club night in King's Cross called Godspeed, which is unusual because it is also dry. "No alcohol and still massively popular!" he boasts. "You wouldn't believe how life-affirming it is to be in a club where there is no animosity, no attitude, no arseholes." He is also entering into artist management, and is convinced that his first discovery, a singer called Coby Koehl who initially contacted George through Facebook, is the greatest modern soul singer since Amy Winehouse. "He is absolutely amazing. A voice to die for."

It is good to be busy, he says. It suits him. And it might just keep him on the straight and narrow.

"Will I ever relapse again?" he asks. "I hope not, no. To be honest, it would be crazy to at this point. I've put so many people through so much drama, so much torture, especially my family, and I don't think I could live with myself if I ever did that to them again." For the first time this afternoon, he doesn't follow a serious thought with the levity of false laughter. His face remains straight. "To let those people down is something I simply cannot consider any more."

Interview over, we walk up the dark aisle of the theatre, and back towards daylight. "You never hear about people successfully being in recovery, do you?" he laments. "You only hear about people being fucked up. But there are many people in recovery all the time, and a great many of them do manage to stay clean, to do good, to sort out their lives. I should know. I'm one of them."

'Amazing Grace', is out now on Decode Records. Boy George is touring the UK until 27 April (boygeorgeuk.com). 'Worried About the Boy' will be broadcast on BBC2 in May

<script type="text/javascript"></script>

Hot off the heels of his latest single, "Amazing Grace", the 'culture' legend that is Boy George has joined forces with us to deliver his spin on the song, "Someone Else's Eyes" by Amanda Lear feat. Deadstar, which opens Amanda's forthcoming new album, "Brief Encounters - Reloaded".

Hot off the heels of his latest single, "Amazing Grace", the 'culture' legend that is Boy George has joined forces with us to deliver his spin on the song, "Someone Else's Eyes" by Amanda Lear feat. Deadstar, which opens Amanda's forthcoming new album, "Brief Encounters - Reloaded".