-

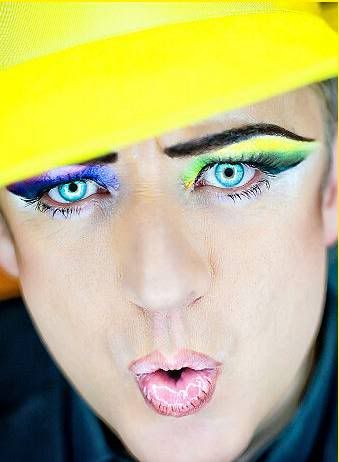

GLAS SPIDER AND DJ Boy George comes to Avaland LE 24 FEVRIER 2006

George, selon agenda, s'est produit en tant que DJ à Sunderland au GLAS SPIDER en Angleterre le 24 février dernier.

INTERVIEW :

At 39, he’s already lived a full life — pop singing star, recovering heroin addict, best-selling memoirist, record producer and impresario, radio-show host, and creator of an upcoming musical. Yet George O’Dowd still likes to be called “Boy.”

These days, Boy George would rather be known for his work as one of England’s top DJs than as the former fringed frontman of quintessential ’80s band Culture Club. Although Culture Club enjoyed a successful brief reunion a couple years ago, George has spent most of the last decade reinventing himself as a top spinner in London clubs. The fruit of his labor can be heard on the new Essential Mix (London-Sire), an hour-plus party of 17 dance tracks performed by George’s friends and discoveries (Kinky Roland, Colein, Amanda Ghost). Although he sings on one track (offering his famous white-soul croon on a dub-oriented remix of “See Thru,” from the recent Culture Club reunion), he’d much rather dazzle listeners with his ability to segue from house to trance to breakbeat and back, all on grooves immaculate enough to eat off.

Boy George has seldom brought his turntables to America, but now he’s doing a high-profile DJ tour that will arrive this Saturday at Avalon to celebrate the third anniversary of the club’s “Avaland” series, which has made Boston a regular stop for international DJ talents including, most recently, John Digweed, Dave Ralph, and Luke Slater. On the phone from London, he speaks freely about such topics as his disdain for ’80s nostalgia, Grammy odd couple Eminem and Elton John, and a lifetime of (as he puts it) pissing people off.

Q: After so many years as a successful European DJ, why are you only now touring America?

A: I’ve actually been to America to DJ, mostly for fashion things and corporate parties. One of the problems with the DJ thing is, when people try to book me, they don’t take into account that I actually need a waiver to get into America, not a visa. A waiver is a government thing that takes two months to get together. DJing isn’t planned that far ahead, really.

Q: Why do you need a waiver and not a visa?

A: Because I’m a convicted drug addict. I have two drug convictions, even though they’re 15 years old. If I were a terrorist, I’d probably be okay.

Q: How would you describe your DJing technique?

A: When you’re playing in a packed club, you have to make sure people keep dancing, so you can’t suddenly drop in a two-step record or a bit of hip-hop. You have to cater to the crowd. But I always play what I like. I don’t necessarily pay attention to what’s in the dance charts. I play progressive house music. But that can vary. That’s why you have faders on the record players, so you can speed things up and down. But if you have one DJ after another who’s playing 180 bpm, you are limited in what you can follow with. You can build things down or up, but you can’t follow a DJ who’s playing techno and drop a garage record, because that would just clear the dance floor. So there’s a bit of a science in watching what the crowd is doing. I’m into everything. I know you have trance DJs or DJs who play this or that. I just like good music.

I do a radio show in the UK as well, called Clubversive, and obviously I can play anything I like as long as it’s dance-floor-oriented. So I can be more experimental than I can be in a club.

Q: Do you still have any interest in mainstream pop?

A: That’s a sort of strange question: “Do you have any interest?” You sound like a bank manager. I think of myself as a creative person. Since leaving Culture Club, I’ve made quite a few albums, and I’ve toured as a solo artist. It’s not like I’m selling peas or something. Pop music has become a dirty word, really, although I’ve made pop music. When you think of pop now, you think of something insipid and cheesy and lacking any kind of emotion or heart. So I have no interest in that kind of pop music. I do like the organic variety, a bit of dirt on it. I don’t really think of myself as being a pop star anymore. It means something different now.

Q: How so?

A: Well, for a start, I always dressed myself and still do. When you do these TV shows, Top of the Pops, for example, the corridors are brimming with stylists and choreographers. The ’90s has really been the revenge of the stylist and the choreographer. Bands don’t really have any social or sexual agenda anymore. You have 16-year-old girls singing about having their hearts broken. It’s just not practical or realistic. The pop scene is like some kind of Christian conspiracy. If you were a Christian organization that wanted to make pop really safe and unthreatening, that’s how it would be right now.

Q: What about more threatening acts, like Eminem?

A: Well, Eminem is pop, really. It’s a cartoon. It’s repetitive. “My name is, my name is.” There’s definitely some kind of intellect there, but it’s very brattish. If you are three years old, you could really remember “My name is” because he keeps saying it the whole time. “Please stand up, please stand up.” It’s perfect for potty training.

Q: What do you suppose he wants to do with Elton John, of all people, at the Grammys?

A: Probably bugger him.

Q: Thinking of the two of them performing together just blows my mind.

A: Maybe they’re going to blow each other.

Q: What do people in England think of honorary Briton Madonna these days?

A: There are people who worship her and people who just think she should fuck off. That’s always been the case. Popularity breeds contempt. Gay people love her, of course. They think she’s just the most important thing since condoms. A lot of other people think she’s talentless and wish she’d just sod off to America. I’m a fan. She reminds me of a grand queen who sits on the throne and clicks her fingers and the furniture maker comes, and the hairdresser comes, and the top producer comes.

Q: What does it say that so many ’80s stars — Madonna, Duran Duran, you — are still making music?

A: I don’t know. There are people still touring who were around in the ’60s. There’s always a certain number of people who want to hold onto the past. There’s always work out there if you want it. From my point of view, it’s important to respect the past, but if I had to spend the rest of my life playing Culture Club songs, I’d go insane. If you’re doing it for the camp or to make a bit of money, that’s fine. But if you have to do it, if you have nothing else going for you, and you just keep chugging out your old songs, I don’t know, I’d probably take up farming.

Q: Is there an age limit for pop musicians?

A: If you look at the current pop scene, it proves that young people don’t have a monopoly on ideas. There’s this television show Pop Stars where they’re auditioning these kids to be pop stars. If you look at the criteria of these people, it’s “I will succeed” and “I will be a star.” I didn’t think like that when I was 14. I didn’t go around saying, “I want to succeed.” I just wanted to piss people off. If you go back to punk or Bowie, people wanted to succeed in upsetting you. Now, being a musician has become a career opportunity.

Q: Is that why you became a musician, to upset people?

A: My whole existence was a way of reacting to growing up in an environment that didn’t accommodate me. From about five years old, I was being called a pouf. I didn’t even know what it meant. Because I was effeminate and pretty, like a girl, I was made to feel like an outsider. So I became one. Of course, I know I’m not, now. I can intellectualize it as an adult. But as a child, you don’t have that luxury. Growing up and being called names at school, you either disappear into the crowd or you stand out, and I chose to stand out. Being a musician and whatever I’ve done in my life is connected to that. I didn’t start Culture Club and think, “I’m going to dominate the world.” I was just happy to have a gig and make a record. People have much bigger expectations now because they know what can happen. It just didn’t cross my mind at 15 that I was going to be famous. I wouldn’t have minded it, but I didn’t plan it.

Q: A lot of musicians say they went into the business in order to get laid.

A: Really? That’s not what happened in my case. David Bowie said something recently, that the whole rock-and-roll ideal has been demystified now. People don’t give a shit. Pop music’s just another commodity now, like a tin of beans. People who go to gigs know everything that’s going on now. They know the ins and outs. When I was a kid going to see David Bowie or whoever, it was always such a mystery, such a fantasy realm. But now, people are just indifferent. The glamor has gone out of it. We live in this period where the industry just has far too much control. The industry’s not really run by creative people. It’s run by bankers in jeans. At the moment, they have just too much say over what people do creatively. That’s a bit depressing. So I have no idea what the next revolution will be. Probably it will be thinking. People thinking for themselves, DIY, doing things for themselves, not caring if they make money out of them.

Q: Of all your accomplishments, what are you most proud of?

A: I’m proud I made difference in people’s lives. People come up to me and say I made it easier for them to be queer or just to be comfortable with who they were, whether they were just fat or different or gay or straight. In some way, I’ve made people more aware of sexual differences, and that’s a good thing. Every drag queen in the world loves me now, so that’s quite good. I’m the granddaddy of drag queens. I’m quite proud of that.

Q: How do you want to be received in American clubs?

A: I’d like people to come and dance rather than stare at me. When I first started to DJ in England, I really had to battle against people expecting me to sing “Karma Chameleon.” I just hope that doesn’t happen in America. We’ll try to have as much fun as possible.

Boy George spins at Avalon for the Avaland third-anniversary celebration this Saturday, February 24. Call 262-2424.

-

Commentaires