-

The Sunday times magazine DIMANCHE 12 NOVEMBRE 2006

They were about sex and they were graphic. Why should I care if Culture Club have re-formed and they're doing my songs? What, on a tour of Butlins? I'm a terrible grudge-bearer, but I forgive eventually, he says, although his fall-outs have been epic.

He hadn't spoken to his father for three years when he died, because of the way he left his mother after 43 years of marriage. He had a heart attack while he was on holiday in Egypt with his new wife. George wasn't going to go to the funeral but a friend persuaded him. Don't get me wrong. I loved my father. But I came back for my mother. It was hard to see her at the funeral with my dad's new wife there. Two months later my mother did a private ceremony and laid a plaque for him. I thought, You are an amazing woman...' I couldn't have loved her more at this point because she did this after everything he did to her. My mother is a tank, a goddess. My dad was a terrible father and a terrible husband, but he did have this really sweet side.

Now the family think he may have been a schizophrenic. George is the middle child of six children. After him came Gerald, who had his father's colouring, good looks and mental problems. He did everything my dad wanted. My dad broke his spirit. The tragedy of my brother was that he is a lovely person and nobody realised he is a schizophrenic. Gerald stabbed his wife to death in 1995 while she was sleeping and was detained under the Mental Health Act.

George's brother David sold the stories of George's drug abuse to The Sun to shock him into giving up his heroin addiction. He tried to save my life. My brother loves me, but it's safe to say that at that period in my history no one was really behaving well. George grew up and in a way still is surrounded by topsy-turvy emotions where love and control are confused.

When George first came out it was his father who understood first, despite his obvious faults. Don't tell me what to do, because I had a father who controlled my every move as a child. I hate authority, yet at the same time it turns me on.

Do you think your father created the blueprint for the ambiguous relationship, the unavailable man? Ha, that's a myth. They're not unavailable. For a start, I've slept with most of the men I've photographed. My mother asked me recently, Where's this relationship going?' I said, Where did yours go? My father left you after 43 years. Where's anything going?' Then she slapped me.

Would you rather want something, have that yearning, than actually have it be kept wanting? Everybody would. How many people are living out there without intimacy? I'm not. But I'm always with the one that's not going anywhere.

For him, it seems, intimacy only happens with insecurity. The idea of gay marriage makes me retch. One of the luxuries about being homosexual is not having to worry about that. I don't want company. I don't want a boyfriend who's a Ming vase. I have friends who are couples who don't have sex. If you ain't having sex, out the door. I don't believe in this whole idea that it's nice to have someone around. It's not.

Recently he hit the headlines again, this time for sweeping the streets of New York on community service. He calls it media service. No quiet park and leaves to bag for him, but a full-on paparazzo frenzy in Chinatown. It was meant to be a humiliation, a public example: even the feted fall. But George remains defiant.

The details of the arrest at his New York flat are traumatic and purposely vague. In October 2005 he called the NYPD, saying his apartment in Little Italy was being broken into. When the cops arrived they found no evidence of a break-in, only a bleary, out-of-it George. They found drugs some reports say 15 small bags of cocaine but their over-eagerness to search the place without a warrant rendered any drugs charges null and void. He was, however, found guilty of wasting police time. It was a crime against myself, says George, who has always defined himself by nearly destroying himself. Ultimately, he's a survivor. He just can't enjoy an easy life.

He's outside my front door smoking a cigarette. It'll be a very short interview if I can't smoke inside, he quips. I never told him he couldn't. I've known George for many years. He's been close to people I've been close to. He's always had turbulent relationships. I've seen him be passionately hot and cold, particularly with women. He has often put them on a pedestal, only to knock them into the ground. The singer and songwriter Amanda Ghost has been his most enduring friend. She's been the only one strong enough to stand up to him.

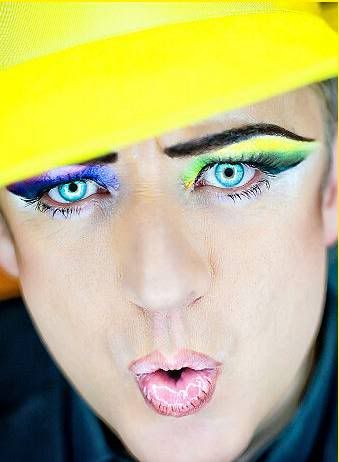

He comes in, sits down. His face is free of make-up, save beautifully pencilled eyebrows. He's in a hoodie and sweatpants from his own range, B-Rude. He's more aggravated by a recent TV documentary than he was by sweeping the streets. They showed nothing about what I'm doing creatively. They played Time Machine, his new single with Ghost, a haunting, soulful ballad. They showed his photography or rather, a photo of a man's penis. Of course there's a lot of homoeroticism in my work, but I have photographs of lots of women too.

It annoyed me, because when I did my service they were telling me, You're a genius, a genius.' But it's not George's genius that makes him fascinating, it's the fact that he couples it with being self-destructive, out of control, scorchingly funny, self-deprecating, bitter, sweet, clever, stupid, wounded and outraged. You can't really humiliate George: he's done too good a job of that himself. His lips curl: How many shots do you need of someone sweeping the streets? I found it very unfascinating. It was surreal, but not boring. There was one girl we kept calling Princess she'd stolen a bottle of perfume. She turned up with her Prada handbag. She was on really good money, but she'd done it to compensate for whatever she wasn't getting emotionally. She made me laugh because she kept moaning the whole time.

Of course, George found camaraderie and softness in the hardest places. It doesn't sound like he found it in the least bit humiliating.

It was about refusing to be humiliated. I'm not Madonna, I don't live that kind of life. We were really working. I didn't mind doing something productive. I wanted to get it over with. I didn't want to talk about my drug arrest either: it's my drama, nobody's business.

Drugs nearly killed him the first time round.

His brother David outed him to Fleet Street, where The Sun ran the headline that he only had weeks to live. That was in 1986, and he's still here. He's survived various friends' deaths by drugs. Got sober and wrote the partly autobiographical musical Taboo, which was about suburban boys experimenting with drugs and sexuality. The musical did well in London in 2001. The next year it was picked up by Rosie O'Donnell to be put on Broadway. Although George questioned whether the hugely successful multimillionaire talk-show host could really connect to the spirit of the funny, sad, decadent musical, he went with it and took on the role of the outlandish club eccentric Leigh Bowery.

After a three-month run it was deemed a flop and she pulled it. George was deeply wounded by the experience. Rosie said she wouldn't change anything, then went about changing everything. She wasn't used to people answering her back. She'd say, Come on, show me your balls.' And if you did, she'd cut them off.

He's chuckling because there's a happy ending to the Taboo story. It's just been bought by Endemol, which owns theatres all over the world, and is going to tour. I prayed every day she wouldn't renew her option. Hallelujah.

But the show's demise left him vulnerable. I stayed in New York, isolating myself and left to my own devices, working on fashion, selling clothes in Pat Fields [the designer made famous for styling Sex and the City]. His New York sojourn mirrored the decadent adventure of 20 years earlier, when he had his first swanky New York apartment, as Culture Club was falling apart and he began his drugs spiral.

Just like the last time, he didn't want to return to London a famous failure. He further isolated himself by firing his manager of 26 years, Tony Gordon, who wanted him to do another Culture Club tour. I'm not interested in living in the past, but he'd sell his soul for a cheeseburger. He wasn't interested in my photography or my fashion. This summer, Culture Club re-formed with a new singer and Tony Gordon as manager. It was a hard thing. I'd been with him since I was 18, but it was a kind of meltdown a lot of other people went out of my life as well.

While he can dismiss the street-sweeping as surreal, his state of mind around the time of the arrest and the arrest itself bring back a wincing pain. He recalls: I was taken to the police station but my foot was bleeding. I'd cut it on something. And you know what Americans are like... They said, He's bleeding, maybe he's got Aids.' So they took me to Bellevue, he chuckles painfully, where I belong. Bellevue is a mental institution for the criminally insane. It was the most nightmarish thing that had ever happened. I was handcuffed to a metal bed. I asked for a drink of water but they just ignored me. I thought, I'll just do a really dramatic scream.

That worked. A really nice Australian nurse came over and said, Are you okay?' I said, I'm not okay. I'm having palpitations, I'm terrified.' Récemment il a engendré des gros titres, cette fois pour balayer les rues de New York au service de communauté. Il l'appelle "service de médias". Aucuns parcs a nettoyer, mais il a tranquillement nettoyé Chinatown sous la frénésie des paparazzis. Cela a censé être une humiliation, un exemple public : même la promesse de faire la fête. Mais George reste provoquant. Les détails de l'arrestation à son appartement de New York sont des traumatismes . En octobre 2005 il a appelé le NYPD, pour dire que son appartement du quartier de Littlle Italie était cambriolé. Quand les policiers sont arrivés, ils n'ont trouvé aucune trace de cambriolage, seulement ce qui allait être un problème pour George. Ils ont trouvé des sachets de drogues - des rapports de police disent 15 petits sacs de cocaïne - mais leur ardeur pour rechercher à qui était le la drogue et l'endroit d’où elle venait fut vaine . Il était, cependant, reconnu coupable d’avoir fait perdre du temps à la police. "C'était un crime contre moi," dit George, qui s'est toujours défini en se détruisant presque. Finalement, il est un survivant. Il ne peut pas juste apprécier une vie facile. Il est dehors devant ma porte pour fumer une cigarette. "Ce sera une entrevue très courte si je ne peux pas fumer à l'intérieur," raille-t-il. Je ne lui ai jamais dit qu'il ne pourrait pas. J'ai connu George pendant de nombreuses années. Il est été près des personnes que j'ai connues aussi de prés. Il a toujours eu des rapports turbulents avec eux. Je l'ai vu être passionnément chaud et froid, en particulier avec des femmes. Il les a souvent mises sur un piédestal, seulement pour ensuite les rabaisser vers le sol. La chanteuse et parolière Amanda Ghost a été résistante à son ami. Elle a été la seule assez forte pour lui tenir tête.

Il entre, s'assied. Son visage est exempt de maquillage, ses sourcils admirablement dessinés au crayon. Il est dans une tenue de sa propre collection, B-rude. Il est d’avantage blessé par un documentaire de TV récement paru sur Channel 4 où il balayait les rues. "Ils n'ont rien montré sur ce que je faisait créativement." Ils ont joué la machine du temps, en choisissent mon fantôme, une hantise, une ballade émouvante. Ils ont montré une photographie prise par lui - ou plutôt, une photo du pénis d'un homme. "naturellement il y a beaucoup d’homo-érotisme dans mon travail, mais j'ai pris aussi des photographies d'un bon nombre de femmes . "Ce qui m'a gêné c’est quand j'ai fait mon service de communauté ils me disaient, ` que vous êtes un génie, un génie.' "mais ce n'est pas le génie de George qui les fait fascinaient, c’était le fait qu'il mélangeait un être suicidaire, hors norme, terriblement drôle, pratiquant l’art de l'auto dérision, amer, doux, intelligent, stupide, blessé et outragé. Vous ne pouvez pas vraiment humilier George : il était surréaliste. Je ne suis pas Madonna, je ne vis pas ce genre de vie. Nous travaillions vraiment. Je ne me suis pas occupé de faire quelque chose de productif. J'ai voulu obtenir plus avec. Je n'ai pas voulu parler de mon arrestation et de la drogue: c'est mon drame, personnel " .Les drogues l'ont presque tué la première fois. Son frère David l’a dénoncé, et a dit qu’il avait seulement quelques semaines à vivre. C’était en 1986, et il est toujours vivant. Il y a eu des décès de divers amis qui n’ont pas survécu à la drogue. Devenu sobre il a écrit la comédie musicale « Taboo » partiellement autobiographique, qui était au sujet des garçons de la nuit qui expérimentaient les drogues et la sexualité. La comédie musicale a eu un beau succès à Londres en 2001. L'année suivante il a été contacté par Rosie O'Donnell mettre « Taboo » sur Broadway. Bien que George ait douté de Rosy pour relayer l'esprit musical drôle, triste, décadent, il a collaboré avec elle et a pris le rôle de l’excentrique Leigh Bowery. Après trois mois de représentations, il a constaté l’échec de la comédie et cet échec a profondément touché George. "Rosie a indiqué qu'elle ne changerait rien, puis a voulu tout changer. Il rit quand même parce qu'il y a une fin heureuse à l'histoire de Taboo qui vient juste d’être acheté par Endemol, qui possède des théâtres partout dans le monde, et elle va voyager. "j'ai prié chaque jour pour qu’ils ne changent pas d’avis. Alléluia." Mais la fin de Taboo l'a laissé vulnérable. "Je suis resté à New York, m'isolant et livré à moi même, travaillant la mode avec B-rude, Son séjour à New York a réssucité son aventure décadente 20 ans plus tôt, quand il a eu son premier appartement de luxe à New York, car Culture Club tombait en morceaux et il a commencé la spirale de la drogue. Juste comme la dernière fois, il n'a pas voulu retourner à Londres suite à un éche . Il s'est isolé en rejetant son manager de 26 ans plus âgé, Tony Gordon , qui a voulu faire une autre tournée de Culture Club. "Je ne suis pas intéressé de vivre dans le passé, mais il vendrait son âme pour un cheeseburger. Il n'était pas intéressé par ma photographie ou ma mode." Cet été, Culture Club s’est reformé avec un nouveau chanteur et Tony Gordon comme directeur. "C'était une chose dure. J’ai été avec lui depuis que j'ai eu 18 ans, mais c'était un genre de fusion - un bon nombre de gens sont sorti de ma vie ."

Son état d'esprit autour de la période de l'arrestation et l'arrestation elle-même rapportent une douleur grimaçante. Il se rappelle : "j'ai été conduit au commissariat de police et mon pied saignait. Je m’était coupé sur quelque chose. Et vous connaissez les Américains ... Ils ont dit, ` qu'il saigne, il a peut-être le sida.' Ainsi ils m'ont porté à Bellevue, "il ricane péniblement ." Bellevue est un établissement mental pour criminel aliéné. "C'était la chose la plus cauchemardesque qui s'était jamais produite. J'ai été menotté à un lit en métal. J'ai demandé de l'eau mais ils m'ont juste ignoré. J'ai pensé, je ferai juste un cri perçant vraiment dramatique. Cela a fonctionné. Une infirmière australienne vraiment gentille est venue et dit, ` vous allez bien?' J'ai dit, ` Je ne suis pas bien.

-

Commentaires